Blog

Incident response: Is MTTI the metric that matters most?

Outages hurt. Ask Mark Zuckerberg. At the beginning of October billions of users were unable to access Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram for several hours. Ouch.

Of course, complete outages like Facebook’s are uncommon (although as we were writing this blog, we heard that hundreds of Tesla owners were locked out of their cars due to an outage). Complete outages can be high-profile, but for businesses running digital services the day-to-day incidents are often less absolute: some segment of users may be hitting errors, a particular feature may not be operating correctly, or the service may be performing slowly under heavy load.

For larger businesses running complex digital services at scale, smaller incidents like these can occur on a regular basis. They may not be hitting the headlines but they may be affecting user experience and, at the end of the day, impacting business performance.

To measure the performance of these digital services organizations turn to two common metrics: Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF, or the frequency of incidents) and Mean Time to Resolution (MTTR, or how long it takes to resolve incidents). But do these metrics really tell the full story, and capture the full cost of incidents?

Thus, with the goal of reducing downtime, popular KPIs like the frequency of incidents – MTBF – and time taken to resolve incidents – MTTR – were born. But do these metrics identify where the pain really is?

A third metric – Mean Time to Innocence (MTTI) – is used as a tongue-in-cheek way to describe the goal of individual teams involved in incident response. When they are pulled away from their work and drawn into a war room where the finger-pointing begins, the metric on their mind is: how fast can I prove that this is not my fault?

MTTI is not used seriously as a measure, but when we dig into where the costs of an incident really lie, there is a serious point to be made. Stick with us on this.

What is the true cost of an incident?

Any vendor who helps you improve the reliability of your systems and services loves to point out how much money you can save by avoiding outages: reduce service downtime by X hours, at Y million dollars per hour, that's X * Y dollars saved. The reality is that outages are often less absolute and the costs much harder to determine. A poor user experience can reduce conversions, but the correlation between system performance and business metrics is difficult to measure. But are these the only costs of incidents?

If you were working for Mark Zuckerberg in the early days of Facebook, you were encouraged to cause incidents: "Move fast and break things". His point was that it is more important to deliver new features, new functionality and new value, than it is to have a perfect uptime. Breaking things (outages) cost something, but what is the cost of moving slowly?

In a world of digital transformation where "every company is a software company", moving slowly can mean losing market share to the competition or missing out on a new market opportunity captured by a startup disruptor.

Incidents can slow you down, and moving slowly can mean irrelevance.

MTBF and MTTR look at how often you're failing, but they don't measure how much they're slowing down your dev teams. When dev teams are pulled on to a incident they are not spending time developing or improving.

Here are two costs to incident response that aren't normally measured, but felt by everyone involved:

1. Failing to invest in improvements to fix underlying problems

The amount of time developers spend firefighting is exactly the amount of time being taken away from building “safer houses”. The last thing we want is for developers to be caught up in a vicious cycle, unable to solve the problem long term at the foundational level.

2. delivering new product value more slowly

The more time developers spend firefighting, the less productive they are in terms of delivering new product value. This makes it harder for the business to stay competitive or capitalize on market opportunities.

3. Losing morale

No developer wants to spend all their time firefighting. They would much rather focus on improving the product and delivering new value, not just because it’s what the business needs, but because it’s what they enjoy as engineers. Too much firefighting and not enough time for the “real work” makes for demoralized and bored developers.

We need to be able to answer the question: how much are incidents slowing us down?

How incidents are resolved

Let's quickly recap on the typical incident response scenario: a problem is encountered and reported – often by end users via the service desk, or perhaps from user experience monitoring tool. The issue gets escalated to an individual or team who are responsible for triaging issues. Depending on the organization this could be a dedicated central operations team, service management team or SRE team. At this point, a lot depends on the knowledge of the team triaging: how the system works, the current system behavior and the problem. Best case they know exactly where to look, but worst case is that they have to bring everyone who might know what the problem is onto an incident response call. The more urgent the incident, the more people are brought onto the call. And not just people – higher priority incidents will draw higher expertise onto the call earlier.

At this point it's not necessarily about identifying root cause, but identifying whose problem it is to fix. At the end of the process, the team responsible buckles down to address the issue, and the rest are absolved, but not before having taken a chunk out of their day. From a developer’s point of view, MTTI is how long it takes to get out off that call and return to their other tasks.

A lower 'Mean Time to Innocence' means that developers and other experts are disrupted for less time, and have more time to improve the services or deliver new value.

When it comes to MTTI, zero is a special value

If you've ever worked in an open plan office, then you'll know the cost of being interrupted. It doesn't matter how long the interruption lasts for, the moment you respond to "Hey, can I ask you something?", you've lost valuable focus and train of thought.

It's the same with MTTI. Just by asking an individual or team to get involved you are impacting their ability to deliver their regular work. As soon as the time-to-innocence is non-zero then damage has been done.

The ideal case is that the teams who are not responsible for an incident and can do nothing to help resolve the incident should not be involved.

Knowledge is the answer

Trying to reduce MTTR isn't new, but in larger organizations with complex digital services and many teams, it's critical to route the incident to the right team – not just to lower the time-to-resolution, but to avoid the costs to the business of slowing down development teams by involving them in incident response.

At SquaredUp we believe this is a knowledge problem. The reason for the incident response call is normally knowledge sharing – how the system works, what the dependencies are, and what the status is of each component. If this knowledge sharing can be automated, the call doesn't need to happen.

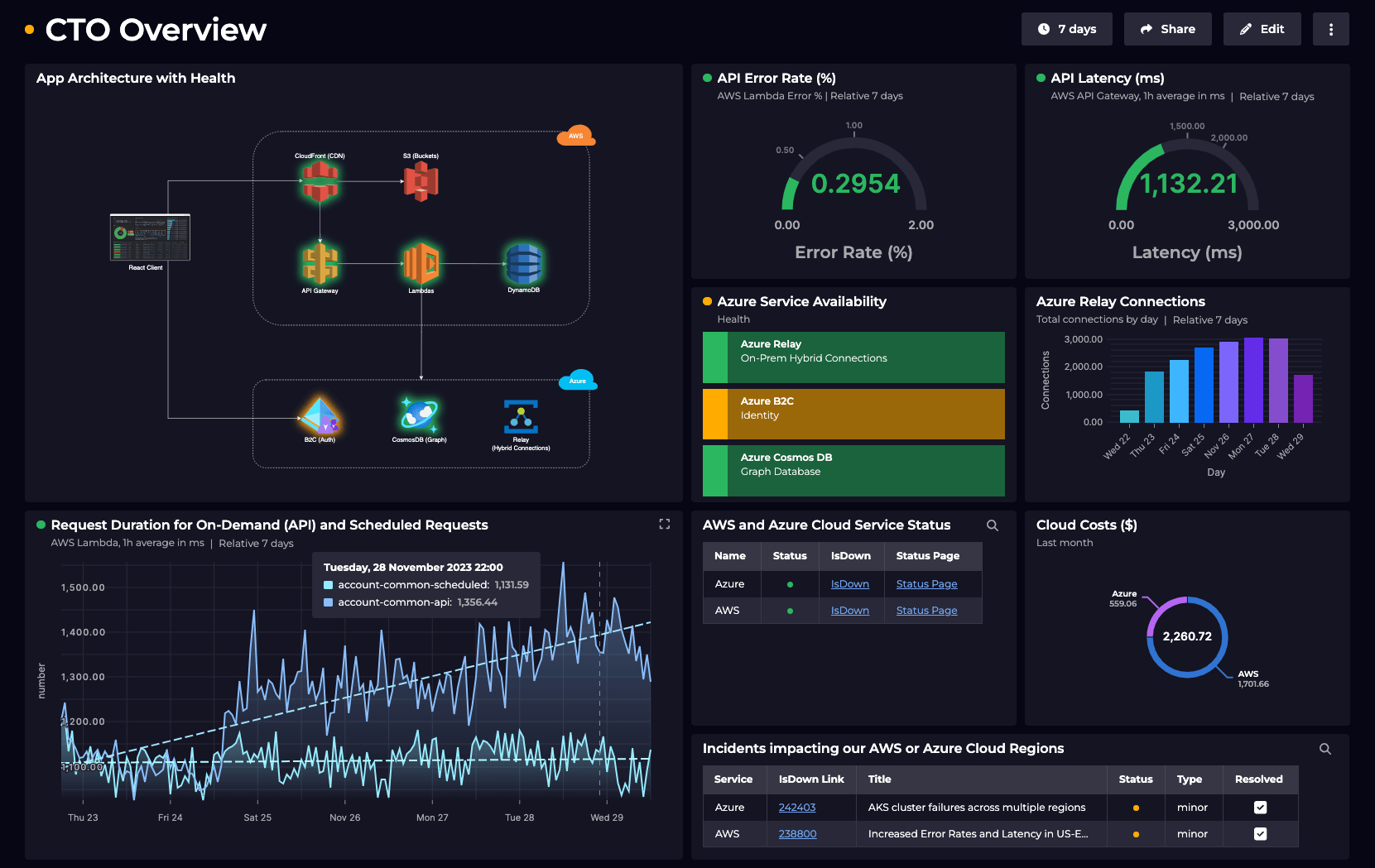

Our approach to this problem is to make sharing knowledge easy. Our observability portal enables each team to capture and share important information about their component – what it is, what it's dependencies are, and what the status is. They can choose to publish any data they need from the tools that they use: key metrics, logs, alerts, documentation, pipeline releases – anything that other teams might need to determine whether the component is where to look for the root cause, or whether the team is 'innocent'.

After all, you want your developers to spend most of their time facing forwards and "moving fast". No doubt Mark Zuckerberg was miffed about the Facebook outage. But he’s probably far more interested in building out the Metaverse.

If you'd like to know more about how the SquaredUp observability portal can reduce your operations MTTR and your developer MTTI, then get in touch for a demo.